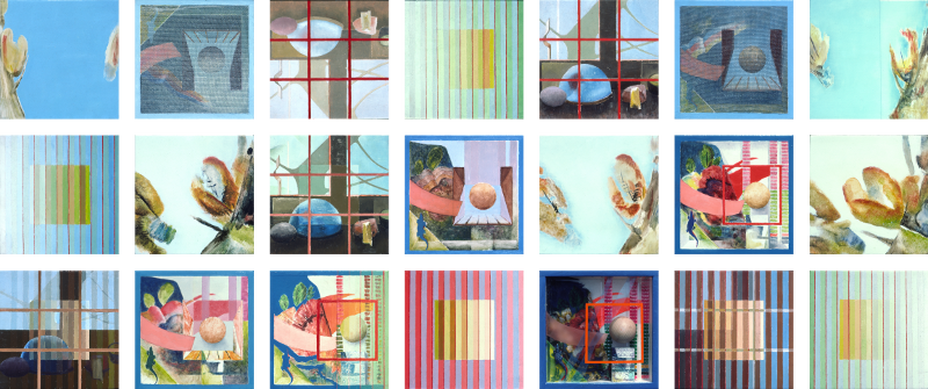

Bloeiwijze 21 (Inflorescence 21), oil on panel, 2,5 D, music composition and AV, ± 1985, Bob van Walderveen

van Walderveen's Tropism

"Tropism is a phenomenon of imperfect coincidence and it reveals itself in the periphery of our perception. It is the origin of our gestures."

Bob van Walderveen (1931-1995) was co-founder of the Tropism. He proclaimed himself a 4D painter.

Noorda's Tropism

Definition

The dictionary definition of tropism is: ‘the ability of an organism to direct itself towards a stimulus’. The most common example is phototropism: the plant's ability to turn towards the light. In ancient Greek ‘tropo' means ‘change’ or ‘turn’.

As an art movement, Tropism both literally and figuratively moves in the direction of a stimulus. Tropism tries to move the observer, while the act of observing itself is being called into question. Every Tropistic work encourages the spectator's ability to turn towards the stimuli that the work evokes.

Tropism can cause rampant confusion in a very clear-cut way. Insights can be lost in broad vistas. Shifts in perception cause expansions of consciousness to condense into contained frameworks where the emphasis falls outside the decoupage.

Tropism is not an ‘ism’ recognisable by certain style characteristics, it is based on a shared philosophy instead. This means that a Tropistic work can be magical realistic, or practically abstract. Tropism moves right across disciplines and techniques. Furthermore, Tropistic expressions are carrier- and media-independent. A text can be Tropistic, or a choreography, or a movie, or an installation. As an art movement it therefore stands slightly apart, and is even slightly separate from the zeitgeist, because of its ability, as a ‘shapeshifter’, to easily evolve into every form of expression. To illustrate this, the series of Tropistic musical compositions from the 80s and 90s of the last century, which clearly have their roots in the minimalist music of the '50s and 60s from the same century, even today, still seem contemporary, or, one might say, they had simply been composed too early.

Because of this strategy, which was not intended as such, Tropism adapts itself effortlessly to any era, because its underlying philosophy is always appealing and therefore timeless. “That essence is the soft-as-down stimulus that makes you jump up from the edge of your chair”, says Noorda. “However, some critics resolutely refuse to see it as an art movement, because of its use of humor, and Tropism, limping on the wrong leg, has stepped on many a critic's toes. But precisely that is Tropism in a nutshell.”

Noorda's Tropism

Definition

The dictionary definition of tropism is: ‘the ability of an organism to direct itself towards a stimulus’. The most common example is phototropism: the plant's ability to turn towards the light. In ancient Greek ‘tropo' means ‘change’ or ‘turn’.

As an art movement, Tropism both literally and figuratively moves in the direction of a stimulus. Tropism tries to move the observer, while the act of observing itself is being called into question. Every Tropistic work encourages the spectator's ability to turn towards the stimuli that the work evokes.

Tropism can cause rampant confusion in a very clear-cut way. Insights can be lost in broad vistas. Shifts in perception cause expansions of consciousness to condense into contained frameworks where the emphasis falls outside the decoupage.

Tropism is not an ‘ism’ recognisable by certain style characteristics, it is based on a shared philosophy instead. This means that a Tropistic work can be magical realistic, or practically abstract. Tropism moves right across disciplines and techniques. Furthermore, Tropistic expressions are carrier- and media-independent. A text can be Tropistic, or a choreography, or a movie, or an installation. As an art movement it therefore stands slightly apart, and is even slightly separate from the zeitgeist, because of its ability, as a ‘shapeshifter’, to easily evolve into every form of expression. To illustrate this, the series of Tropistic musical compositions from the 80s and 90s of the last century, which clearly have their roots in the minimalist music of the '50s and 60s from the same century, even today, still seem contemporary, or, one might say, they had simply been composed too early.

Because of this strategy, which was not intended as such, Tropism adapts itself effortlessly to any era, because its underlying philosophy is always appealing and therefore timeless. “That essence is the soft-as-down stimulus that makes you jump up from the edge of your chair”, says Noorda. “However, some critics resolutely refuse to see it as an art movement, because of its use of humor, and Tropism, limping on the wrong leg, has stepped on many a critic's toes. But precisely that is Tropism in a nutshell.”

Tropism appears not to be the apparent, but instead lets the ‘being’ apparently appear. The anglerfish with its angling light, will never reach the stimulus he swims after, but does that mean we should consider it motorically naïve? Stupid, like a dog who pulls a cart, as the child sitting on the cart is dangling a sausage in front of its nose? An evolutionary mistake? He really is blinding himself in the dark depths, and anyone who has ever walked into a cave with a flashlight turned towards his face, knows how dangerous that is. Blinding yourself in the dark makes for bad navigation. But, as always, it is the encounters on the road that matter, instead of the reaching the destination. In the land of deep darkness, the anglerfish that is blinding itself, is nevertheless king among the seeing: the unsuspecting prey fish that are attracted by the light. At which point the anglerfish gratefully eats them. So the moral of this story is, that it is precisely this blind navigation that can make roast pigeons fly straight into our mouths, so to speak.

And so Tropism connects the irreversibility of the notion of entropy with the causally inexplicable connectedness of Jung's synchronicity. And that is why the anglerfish is a prime example of Natural Tropism.

Natural Tropism

So Tropists have an affinity with plants, greenery, nature, sunlight, the clouds, the sky, and the insects that whizz around light sources. And the remarkable behaviour of our fellow creatures that is shown in, for example, nature documentaries by David Attenbourough, is a welcome source of inspiration for Tropists.

Especially remarkable is the way biological tropism works in plants. When a plant grows towards the light, it is actually the inhibition of growth that occurs on the sunlit part of the plant that causes it to bend. Because the cells in those areas remain small, the plant curves towards the light. One would expect the light to stimulate growth, but it is the other way around and that causes the bending towards the light. It is this perverse and unexpected mechanism that ultimately characterises Tropism.

In nature, gravitropy (direction of growth affected by gravity), and phototropy (direction of growth affected by light) are the two most common forms of tropism in plants. A rare example of a mix of gravitropy and phototropy, while still producing a uniform direction of growth, can be found among the remains of a Roman cellar in the Archaeological Park of Baia in Italy, where a small tree grows upside down.

Tropism can exist in nature, also as art manifestations, without conscious interference of man, this is the so-called ‘Natural Tropism’. In 1984, the three founders of Tropism photographed a classic example of this during one of the first pre-Tropistic field expeditions to the ruins of Fort Tienhoven near Maarssen (NL). In one corner of the exterior of the building there had once been a drainpipe, as could be concluded from the brackets that were still there. The drainpipe itself had decayed or been looted for its zinc. Curiously, a tree had grown there, which had made excellent use of the drainpipe brackets. The tree had grown though the brackets. This is true Natural Tropism. Whatever possessed that tree? Was it looking for support? Was it having an identity crisis, actually preferring to go through life as a drainpipe? What pulled her into those brackets, a tree-fetish for bondage bonsai? It are these existentialist questions that characterise Tropism.

Tropism can exist in nature, also as art manifestations, without conscious interference of man, this is the so-called ‘Natural Tropism’. In 1984, the three founders of Tropism photographed a classic example of this during one of the first pre-Tropistic field expeditions to the ruins of Fort Tienhoven near Maarssen (NL). In one corner of the exterior of the building there had once been a drainpipe, as could be concluded from the brackets that were still there. The drainpipe itself had decayed or been looted for its zinc. Curiously, a tree had grown there, which had made excellent use of the drainpipe brackets. The tree had grown though the brackets. This is true Natural Tropism. Whatever possessed that tree? Was it looking for support? Was it having an identity crisis, actually preferring to go through life as a drainpipe? What pulled her into those brackets, a tree-fetish for bondage bonsai? It are these existentialist questions that characterise Tropism.

Some years before, in a French vegetable shop somewhere in Provence, Robin Noorda found a tomato with a protruding phallus-like part. The next day, at the same greengrocer, he found the female counterpart. “I was so happy that the first tomato had not ended up in the ratatouille yet, so I could photograph the two phenomena together,” says Robin. These manifestations, strongly reminiscent of the voluptuous Neolthic fertility figurines, illustrate the more tangible-absurdist form of Natural Tropism.

As we define the biological meaning of tropism by the ability of an organism to direct itself towards a stimulus, we could say that the erection of a phallus is tropism in full action during which the polarity of forces evokes a pendular movement that sustains the stimulus. The entropy of it can only be explained by the ejaculation of life that multiplies by division. (LOL)

Than again, phallus worship is one sided, polarity connects and therefor the opposite is always true.

An even older example of Natural Tropism is the stone that ‘caught’ another stone. The waves of the surf had swept a small stone into the hollow of a large flint stone causing it to be stuck in that hole forever.

From a philosophical point of view, the stone with stone is interesting. A stone with a hole, meeting an other stone that fits exactly in that hole, is very unlikely. The chances of the small stone then being manoeuvred into that hole by the waves is, according to the laws of probability, overwhelmingly remote. It is easy to explain how the small stone got stuck in the hollow of the large stone. Yet it is impossible to explain that it got stuck there. This is fundamental Natural Tropism.

Tropism re-emerged

A certain Cicada species, the Magicicada, stays dormant underground for 17 years, in a kind of hibernation, after which they suddenly all wake up together. This appears to be the case with Tropism as well. The first Tropistic wave started in 1984 and faded out in 1995 after co-founder Bob van Walderveen died. After having slumbered for 17 years in our heads, Tropism has re-emerged again in 2012 and is stronger than ever. Tropism seems unstoppable, the stimulus is too strong. The delicate fungi spores have been spread throughout the forrest, under the blankets of leaves, and sure enough, fairy rings, fungi and boletes are appearing everywhere. Many people now call themselves Tropists or adopt the name Tropism. The philosophy takes root, infected and tainted, consciously and unconsciously, as rampant graffiti in the caverns of our minds.

Origin of Tropism

Dada

Dadaism was an anti-First-World movement, opposing the establishment. Marcel Duchamp has said that art is not only created by the artist, but that the viewer is the actual connection to the outside world. Surrealism, having emerged from Dada, was characterised by founder André Breton as a revolutionary movement as well. Fluxus was perhaps even more rebellious. The first sentence in the Fluxus Manifesto states: “Purge the world of ‘bourgeois sickness’, intellectual, professional and commercialised culture”.

Like Duchamps dadaism, Tropism is about involving the spectator, and even calling this involvement into question. Tropism, however, protests against revolution, because, as the word itself suggests, this is a repetitive movement. And repetition does not please us, it is a tedious and continuous recursion which we will only accept in minimal music. This, however, in no way implies that Tropism is conservative. Tropism stands for the intuitive impulse, improvisation, and the intrinsic initiative, where the road is taken before it has been travelled on. Tropism wants to promote original, clear, direct and uniform motion towards the true and bright goal of enlightenment, even if this is artificial light.

Entropy

Tropism makes use of entropy. Wikipedia: “entropy, in thermodynamics, is a measure of energy in a thermodynamic system, which is not available for useful work - entropy, in information theory, is the measure for information density in a series of events. Information arises when an event occurs of which it was uncertain whether it would actually take place.” Tropism speculates on these concepts of uselessness, uncertainty and elusive potential, and is guided by the certainty of chance.

Entropy in art can, in the elaborate manner of the American ‘land art’ artist Robert Smithson (1938-1973) who adopted this notion, be seen as a pre-Tropistic clue.

However, Smithson did not use the word Tropism yet. Suzi Gablik, born in 1934 in New York, did. One of her works from 1972 titled Tropism # 12, is a combination of photo collage and oil on canvas (61 x 61 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum). She used the interpretation of entropy as the crash of a system, and saw, in the era of modernism, the collapse of boundaries and the loss of values, and drew from this stimulus and engagement.

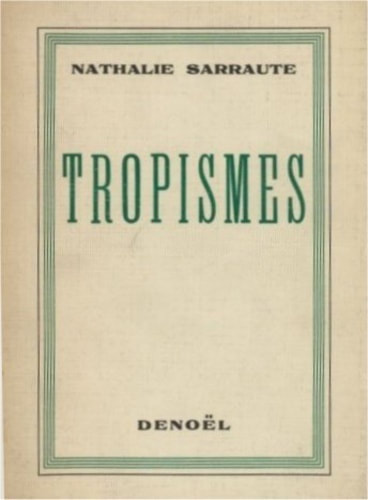

Nouveau Roman

In the 1950's, connected, but prior to the Nouvelle Vague film movement, the French literary movement ‘Nouveau Roman’ emerged. The first work that is attributed to Nouveau Roman is the novel ‘Tropismes’ by Nathalie Sarraute. It was her debut, written in 1932 and published in 1939. With her ‘Tropismes’ she refers to inner movements of the spirit, that are involuntary and that guide us in our behaviour. Tropism Co-founder Bob van Walderveen had been inspired by this book when he defined Tropism in 1986 as follows: “Tropism is a phenomenon of imperfect coincidence and it reveals itself in the periphery of our perception. It is the source of our gestures.”

Tropismes, 1932 - Nathalie Sarraute

Zero Movement

Some critics stated that Tropism was also connected and influenced by the Zero movement that started in 1958. Why paint with a brush? You could also create shapes with other materials, right? The three-dimensional (Tinguely) made its appearance. Why does a painting have to consist of paint only? One has to let go of the old; go all the way to 0. Create something new from scratch. The name ZERO referred to the countdown to the launch of a rocket and thus to a new beginning and a positive future. The Dutch Zero movement made 'anti-painterly' work and made use of industrial materials. Early tropism painter Bob van Walderveen also used all kind of industrial materials in his 2,5D paintings.

There might be an analogy between the direction of a rocked launch and the movement triggered by a stimulus, like the tropism phenomena as in the movement of a plant in the direction of the light. The erection of a fallus is a hard and a persistent manifestation with a clear will of its own regardless it being made of industrial material or organic and living plant material. Eric Idle wrote: You know, you come from nothing. You're going back to nothing. What have you lost? Nothing (from "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life").

The dimension of zero is a point and also a black hole. Yet the the pointless answer to the ultimate question of 'Life, the Universe and Everything' is the sum of three cubes (-80538738812075974³) + 80435758145817515³ + 12602123297335631³ = 42.

When asked, a Tropists might admit there is a connection between: nothingness, humor, lack of paint, stimuli like bright light and the procreation of life itself. So an associative link with the Zero movement can't be ruled out.

Some critics stated that Tropism was also connected and influenced by the Zero movement that started in 1958. Why paint with a brush? You could also create shapes with other materials, right? The three-dimensional (Tinguely) made its appearance. Why does a painting have to consist of paint only? One has to let go of the old; go all the way to 0. Create something new from scratch. The name ZERO referred to the countdown to the launch of a rocket and thus to a new beginning and a positive future. The Dutch Zero movement made 'anti-painterly' work and made use of industrial materials. Early tropism painter Bob van Walderveen also used all kind of industrial materials in his 2,5D paintings.

There might be an analogy between the direction of a rocked launch and the movement triggered by a stimulus, like the tropism phenomena as in the movement of a plant in the direction of the light. The erection of a fallus is a hard and a persistent manifestation with a clear will of its own regardless it being made of industrial material or organic and living plant material. Eric Idle wrote: You know, you come from nothing. You're going back to nothing. What have you lost? Nothing (from "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life").

The dimension of zero is a point and also a black hole. Yet the the pointless answer to the ultimate question of 'Life, the Universe and Everything' is the sum of three cubes (-80538738812075974³) + 80435758145817515³ + 12602123297335631³ = 42.

When asked, a Tropists might admit there is a connection between: nothingness, humor, lack of paint, stimuli like bright light and the procreation of life itself. So an associative link with the Zero movement can't be ruled out.

Marseille's Tropism

Stimuli that get stuck

Tropism gets stuck where others continue. The nature of perception is a main theme in the Tropists work. The Tropists occupy the fringes, where things might or might not be observed. A Tropistic work is about marking that boundary - the place where the visible becomes invisible or where the invisible may just about (fail to) surface; the imperceptible changes that eventually turn a situation completely on its head.

Tropism is intrinsically multidisciplinary, and is not characterized by a particular style or method. The fringes where the Tropists move, border on the humorous. Tropistic works can acquire a humorous dimension through the subtle ambiguities that are hard to pin down.

Tropism is timeless, in the sense that it is possible, and very pleasant too, to detect Tropistic trends in art, literature and philosophy from the past, from Heraclitus to David Hockney. Tropism is also very current and very ‘now’, because it works within the technological culture that defines our time, while at the same time busy discovering its boundaries. Tropists want to drop the viewers into the holes of our technological worldview, and leave them there to contemplate for a while, in a time that always continues in a hurry.

In short: Tropism gets stuck where others continue.

Vision and targets

‘Photosynthesis - Tropism in botanical gardens’ focuses on the artist's vision in its presentation of a series of perceptions with plants and plant-related matters in the lead. The works vary widely in nature and technique, from magic realism and technically basic ‘camera obscura’ photographs by Bethany de Forest to the world's most advanced electron microscope technique as used at Wageningen University.

Everything you see and hear is vegetal, but created by an artist. The artist is the starting point, not the objective scientific view. All works are related to botanical gardens, often having been physically created there. Material from botanical gardens, and references to those gardens, appear in many Tropistic works. Each perception tells a story, sometimes factually educational, sometimes amazingly absurd or fantastically surrealistic.

Tropism likes to put the viewer on the wrong foot by using humour. The viewer is encouraged to verify what he perceives, after which the incredible does appear to be true after all. Despite their differences, all stories and images form a carefully composed unity that strives for a cumulative impression of utter amazement. All this will tap into an exceptional combination of audiences, from young to old, from the poetic dreamer to the rational scientist, from the art lover to the film, media and music lover, from the botanist to the technician, and from the biologist to the philosopher.